I feel pretty confident that my car has the right amount of oil in the engine and air in the tires. Why? because that has been the case every time I check these things. So why bother checking?

Paediatrics is a dangerous speciality because the usual outcome of any child presenting for assessment is that everything is fine. Fever? It's probably an uncomplicated viral infection. Rash? Virus. Lump in the neck? Virus. You get the idea.

As a result, any one of us can become so used to the benign outcome that we don't expect the dangerous problems or the unusual causes of childhood symptoms. This is called availability bias. The last 50 children with this presenting complaint had a virus and got better, so this patient is likely to be the same.

Of course the statement about the likelihood is true, however people don't bring their children to us just for a probability estimate. We are there to assess whether there is a significant problem that requires intervention. To get there, we need to know what to look for.

Abdominal pain in children is a good example. Children often get abdominal pains. One of the most common presentations is abdominal pain during a febrile illness. Most likely cause? Virus. I suspect that the significant pathology that is most often considered in this situation is appendicitis. Appendicitis is relatively rare in younger children but paradoxically more difficult to diagnose, so while the chances of a 3 year old having appendicitis is very low, so are the chances that a 3 year old with appendicitis will get this diagnosed easily.

Appendicitis is at least on our minds and so we're probably not going to miss it through failure to look. There are plenty of causes of abdominal pain that are easily missed for various reasons. Lower lobe pneumonia, for example, is easily missed because it isn't in the abdomen. Testicular torsion is easily missed if it isn't looked for. You'd think that if a child or young person had a problem with their genitalia they might mention that. They often don't. If you don't look for torsion, you won't find it.

Here's a brief overview of some of the easily missed causes of abdominal pain in children:

Here is a more extensive list of possible causes of abdominal pain in children. (1)

Going through these, starting at one o'clock:

Mesenteric Adenitis - Yes, children with viral upper respiratory tract infection can get acute abdominal pains and can even have localised abdominal tenderness. Children with more significant causes of pain can also have URTI, so if there are red flag signs or symptoms you should still take these seriously.

Non-IgE food allergy - This can cause acute abdominal pain but paradoxically is a diagnosis best not made acutely. History, a food diary and follow-up are the way forward when food allergy becomes a possibility.

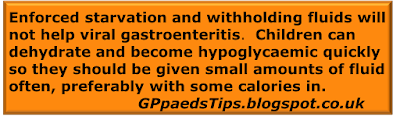

Gastroenteritis - When vomiting precedes abdominal pain then this makes gastroenteritis more likely. Similarly, diarrhoea is a strong indicator of viral enteritis. However, there is no such thing as always, so careful abdominal examination is key and signs that suggest a surgical cause should still lead to referral.

Gynaecological - The main thing to say about this is that it is a common pitfall to forget to even consider this possibility in children. How often do you think ectopic pregnancy is considered in the differential of a 13 year old with acute abdominal pain? It should always be remembered as a possiblity. Do a pregnancy test.

Constipation - This is possibly the most common cause of afebrile acute abdominal pain in children. There are two main pitfalls. The first is to miss the diagnosis because the child or parent doesn't think the child is constipated. The second is to think that because the presentation is acute, the problem just needs a brief period of treatment. If they are constipated enough to present with acute pain, the problem is chronic and should be treated as such as per NICE guidelines.

Urinary Tract Infection - Abdominal pain +/- vomiting without diarrhoea is a common way for children to present with UTI. There is no absolute rule on when and when not to test a urine but it is fair to say that significant diarrhoea usually precludes it for a couple of reasons. In all other cases of acute abdominal pain, it is usually a good idea even if interpreting the result is not completely straightforward.

Colic - Truly a diagnosis of exclusion, but this can be a good history and examination. What to do with colic is covered here.

Appendicitis - Uncommon but not so rare that you won't see a case every now and then. Picking them out from the crowd can be difficult. Good simple analgesia and reassessment after an hour is often a helpful discriminator for the grey cases if you can do that.

Testicular torsion - Inguinal and genital examination is part of the examination of a male presenting with abdominal pain. Do it, even if the last 100 times were normal.

Intussusception - Rare but deadly. Episodes of pallor and signs of being significantly unwell are reasons to suspect intussusception. Bloody and mucousy (recurrent jelly-like) stools make it easier to diagnose but may be a late sign.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis - It is very easy to see how first presentations are initially diagnosed as viral illnesses. If you've got a child who's a bit more lethargic or subdued than your typical gastroenteritis case, or if there is a report of polyuria, test a glucose.

In most cases, significant causes will be excluded by a thorough history and examination. Often a urine test is a good idea and sometimes a second opinion will be necessary. Abdominal X-ray is almost never useful in making a decision about referral.

Paradoxically, the wrong sort of confidence comes from repeated experience of nothing bad happening. The right sort of confidence comes from knowing that bad things will happen and knowing that we're ready for that eventuality. This often happens once you've experienced the sharp end of an unexpected diagnosis. If that has happened, congratulations! You're now an expert.

Edward Snelson

Experienced if not Expert

@sailordoctor

Disclaimer - Experience doesn't always lead to expertise but it's a fairly important element. Bad experience is a good wad to develop great expertise but only if you have all the right elements in place to ensure that you learn without becoming a second victim. I would like to see more work in that area, especially at the Primary/ Secondary Care interface.

Reference

Paediatrics is a dangerous speciality because the usual outcome of any child presenting for assessment is that everything is fine. Fever? It's probably an uncomplicated viral infection. Rash? Virus. Lump in the neck? Virus. You get the idea.

As a result, any one of us can become so used to the benign outcome that we don't expect the dangerous problems or the unusual causes of childhood symptoms. This is called availability bias. The last 50 children with this presenting complaint had a virus and got better, so this patient is likely to be the same.

Of course the statement about the likelihood is true, however people don't bring their children to us just for a probability estimate. We are there to assess whether there is a significant problem that requires intervention. To get there, we need to know what to look for.

Abdominal pain in children is a good example. Children often get abdominal pains. One of the most common presentations is abdominal pain during a febrile illness. Most likely cause? Virus. I suspect that the significant pathology that is most often considered in this situation is appendicitis. Appendicitis is relatively rare in younger children but paradoxically more difficult to diagnose, so while the chances of a 3 year old having appendicitis is very low, so are the chances that a 3 year old with appendicitis will get this diagnosed easily.

Appendicitis is at least on our minds and so we're probably not going to miss it through failure to look. There are plenty of causes of abdominal pain that are easily missed for various reasons. Lower lobe pneumonia, for example, is easily missed because it isn't in the abdomen. Testicular torsion is easily missed if it isn't looked for. You'd think that if a child or young person had a problem with their genitalia they might mention that. They often don't. If you don't look for torsion, you won't find it.

Here's a brief overview of some of the easily missed causes of abdominal pain in children:

Mesenteric Adenitis - Yes, children with viral upper respiratory tract infection can get acute abdominal pains and can even have localised abdominal tenderness. Children with more significant causes of pain can also have URTI, so if there are red flag signs or symptoms you should still take these seriously.

Non-IgE food allergy - This can cause acute abdominal pain but paradoxically is a diagnosis best not made acutely. History, a food diary and follow-up are the way forward when food allergy becomes a possibility.

Gastroenteritis - When vomiting precedes abdominal pain then this makes gastroenteritis more likely. Similarly, diarrhoea is a strong indicator of viral enteritis. However, there is no such thing as always, so careful abdominal examination is key and signs that suggest a surgical cause should still lead to referral.

Gynaecological - The main thing to say about this is that it is a common pitfall to forget to even consider this possibility in children. How often do you think ectopic pregnancy is considered in the differential of a 13 year old with acute abdominal pain? It should always be remembered as a possiblity. Do a pregnancy test.

Constipation - This is possibly the most common cause of afebrile acute abdominal pain in children. There are two main pitfalls. The first is to miss the diagnosis because the child or parent doesn't think the child is constipated. The second is to think that because the presentation is acute, the problem just needs a brief period of treatment. If they are constipated enough to present with acute pain, the problem is chronic and should be treated as such as per NICE guidelines.

Urinary Tract Infection - Abdominal pain +/- vomiting without diarrhoea is a common way for children to present with UTI. There is no absolute rule on when and when not to test a urine but it is fair to say that significant diarrhoea usually precludes it for a couple of reasons. In all other cases of acute abdominal pain, it is usually a good idea even if interpreting the result is not completely straightforward.

Colic - Truly a diagnosis of exclusion, but this can be a good history and examination. What to do with colic is covered here.

Appendicitis - Uncommon but not so rare that you won't see a case every now and then. Picking them out from the crowd can be difficult. Good simple analgesia and reassessment after an hour is often a helpful discriminator for the grey cases if you can do that.

Testicular torsion - Inguinal and genital examination is part of the examination of a male presenting with abdominal pain. Do it, even if the last 100 times were normal.

Intussusception - Rare but deadly. Episodes of pallor and signs of being significantly unwell are reasons to suspect intussusception. Bloody and mucousy (recurrent jelly-like) stools make it easier to diagnose but may be a late sign.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis - It is very easy to see how first presentations are initially diagnosed as viral illnesses. If you've got a child who's a bit more lethargic or subdued than your typical gastroenteritis case, or if there is a report of polyuria, test a glucose.

In most cases, significant causes will be excluded by a thorough history and examination. Often a urine test is a good idea and sometimes a second opinion will be necessary. Abdominal X-ray is almost never useful in making a decision about referral.

Paradoxically, the wrong sort of confidence comes from repeated experience of nothing bad happening. The right sort of confidence comes from knowing that bad things will happen and knowing that we're ready for that eventuality. This often happens once you've experienced the sharp end of an unexpected diagnosis. If that has happened, congratulations! You're now an expert.

Edward Snelson

Experienced if not Expert

@sailordoctor

Disclaimer - Experience doesn't always lead to expertise but it's a fairly important element. Bad experience is a good wad to develop great expertise but only if you have all the right elements in place to ensure that you learn without becoming a second victim. I would like to see more work in that area, especially at the Primary/ Secondary Care interface.

Reference