In the

previous post, I explored how confirmation bias can lead us to believe that something is causing a problem when really it isn't. Although sometimes unexpected, this kind of news is not unwelcome. Finding out that fever doesn't really cause febrile convulsions is a surprise to many, but usually a good one. Telling people that their treatments don't work is much less popular.

Anyone who has been a clinician for a reasonable amount of time knows what it feels like to share good and bad news with someone. When I am teaching about paediatrics in primary care, it sometimes feels like I am saying that very few treatments actually work. This feels having something taken away form us. The real headline is that children make themselves better in the vast majority of clinical scenarios. It is our job as clinicians to do as much nothing as possible while looking for opportunities to give effective treatments.

One question that I am often asked is, "If these treatments don't work, why do people use them?" Good question. I tend to assume that my sample cohort of co-workers is representative of clinicians and I work with good, conscientious people who want to give children the best treatment possible. Since I don't believe that clinicians are generally unintelligent, malicious or lazy, I will take a risk and say that there must be powerful forces at work if any of us are giving ineffective medicines to children. The problem that leads us all to use ineffective treatments is our very desire to make children better and parents happy.

If you want something really badly and do something in an attempt to make it come about, when the thing happens, we are likely to believe that this was cause and effect. This approach would work in a fixed environment, For example, consider a person trying to solve a puzzle (like a Rubik's Cube). The puzzle isn't going to solve itself, so if the person tries many different strategies and then something works, they have solved the puzzle. This assumes that the puzzle has not been solved by chance, which in this case is extremely unlikely.

Now consider someone with a different problem. He wants a picture of his goldfish next to the castle in the goldfish bowl. He tries shining a light to get the goldfish to move into position. He tries tapping the glass, placing some food and tries making waves in the tank. Whatever he does just before the goldfish moves into position must have done the trick right? Wrong.

Well, much of paediatrics is like that. Childhood symptoms often fluctuate or resolve. We want our treatments to work. We want to make children better and parents to be happy. These factors are the perfect ingredients for us to wrongly believe that what we did worked. Sometimes though, the goldfish just moves. Because it's a goldfish.

Enough about goldfish. Let's use a really common example of how confirmation bias leads us and our patients to believe in an effect that is not real.

If I tell someone that antibiotics will cure a child's throat infection within a week, you can imagine how that sounds plausible. Then, the initial belief in my statement will be reinforced when the child does indeed get better. The true believer does not consider that the alternative is just as plausible - that all (uncomplicated) throat infections get better with time. You know that guy who still has the viral sore throat he caught when he was two years old? No? Neither do I.

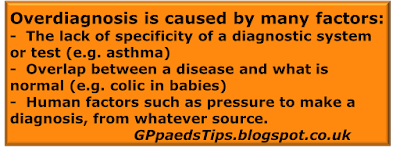

Paediatrics is a branch of medicine where most illnesses will resolve with time and many symptoms that could be attributed to a treatable cause. But we and the parents both want the problem to be treatable. The problem is, you're too nice. You want to help and you want everyone to leave happy. This is called affective bias (the thing that reinforces confirmation bias). The end result is that we can easily believe that we are treating a problem, when in fact it gets better on its own.

Now, bias gets a bad name in medicine, but I would like to defend bias. Clinicians could never learn or make decisions without bias. We would be permanently uncertain and unable to choose. Without confirmation bias, we would never notice a pattern. Without affective bias we would never take the parents seriously or care about the child.

Bias is good. There, I've said it.

Bias is your friend, but friends can be fickle. The thing about friends is that despite their faults, they're still your friends. It is good to know what to expect from them. That way, you don't feel surprised when they do the thing that they always do. In the case of bias, your friend wants to mislead you and get you do do things you shouldn't do.

So, what are the best examples of the confirmation bias of presumed effect in paediatrics? I've already mentioned antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infection. There are many more, but lets just look at one in detail as an example:

Confirmation bias (presumed effect) -

Example number 2: Treatments for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in infants

If there was ever a paediatric condition that fitted the brief for this subject, it is feeding problems in babies. The symptoms that babies present with are so often simply withing normal limits for infancy. Did you know that straining is a thing that 1 in 6 babies do and that it is called

dyschezia, not constipation? If you add regurgitation of milk (aka 'reflux'), colic and other common gastrointestinal complaints, most babies have some sort of symptom that we could treat if we chose to during the first few months of life. With a few exceptions, these are normal for being a baby, and will resolve in time.

The cardinal sign of a self resolving problem is that there are treatments available without good evidence of efficacy. (Cough medicines for children are a good example of this.) By way of contrast, there are very few treatment strategies for the management of pneumonia. I'm guessing that you probably use antibiotics.

The evidence for the available treatments for reflux disease is not good. In many cases the evidence is that they have little effect. Rather than posting several dozen references, I am simply going to signpost you to the

NICE guideline for Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in children and young people. (1) In the full document there is an extensive literature review which makes for interesting reading. The bottom line is that the evidence is usually lacking. The evidence that we do have form research points toward little or no effect for alginates, H2 agonists and PPIs. By their own admission, much of the advice in the guideline depends on the experience of the experts involved in the guideline writing process.

Of course the problem is that there are infants with genuine pathology. These children often begin their visits to healthcare professionals with non-specific presentations which easily fit the bill for what is 'normal for infancy'. If we are honest with ourselves, the niggling doubt that the child might have a significant problem is one of the factors that pushes us in the direction of pulling out our prescription pads. After all, it won't look as bad when the child turns out to have a problem later if we were busy trying treatments instead of reassuring the parent that these symptoms are usually part of normal infancy.

Avoiding unnecessary treatments

is gold standard care. Alginates are the most frequently used medications for reflux symptoms but in my experience this treatment runs a high risk of causing constipation. This is far from ideal if you are trying to make life easier for baby and parent alike. Motility drugs have repeatedly been associated with dangerous cardiac side effects and PPIs have been shown to increase the risk of respiratory tract infection. (2) The take home message from this is that, although medication is an option, we need to be sure that a treatment is really likely to be better than watchful waiting.

The NICE guidelines focus on consideration of how the infant is affected - severe distress or red flags (faltering growth, feed refusal etc.). It is also important to consider other possible diagnoses such as UTI.

I said that there were quite a few problems that have a similar story. Going through all of them in detail would take a long time, but here is a list of some of the treatments that lend themselves to this combined bias effect:

The evidence for all of these treatments in children is that they work rarely (antibiotics for URTI, inhalers for cough alone, suspected CMPA based on colic alone) or never (cough syrups, simethicone or lactase for colic in babies). All of these clinical scenarios share a common theme- the likelihood that the symptom will resolve in time.

So lets come back to bias. Confirmation bias will cause us to believe that a treatment is effective while affective bias will make us want to give something even when there is little or no benefit. "But earlier, you said that bias is good. You said that bias is my friend!" you might well say. I stand by that. As long as you know how you expect your friends to behave, any misbehavior can be managed and they can still be your friends.

For confirmation bias, we need to have good evidence to justify treatment that is used for symptoms when the natural course is resolution with time. For example, I don't need evidence to back up my belief that morphine works for pain when a child has a broken leg. If the child feels less pain afterwards, it has nothing to do with a goldfish effect. Conversely, I should want evidence that a treatment is effective for any of the symptoms listed above.

For affective bias, we need to harness our desire to be nice to parents and children. That means not wasting their time with ineffective treatments or worse still causing new problems. Sometimes, doing nothing is the nicest thing that you can do. Managing to treat where appropriate and avoid unnecessary treatment is the holy grail of paediatrics. Ultimately, the child is the patient and we need to only give them medication that is more likely to help than harm. At least, that's what we should be trying to do despite our biases.

Edward Snelson

Amateur Medical Errorist

@sailordoctor

Disclaimer - I am too biased to be taken seriously, even by myself.

References

- NG1 - Guideline for Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in children and young people, NICE

- Orenstein et al., Multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial assessing the efficacy and safety of proton pump inhibitor lansoprazole in infants with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease, J Pediatr. 2009 Apr;154(4):514-520