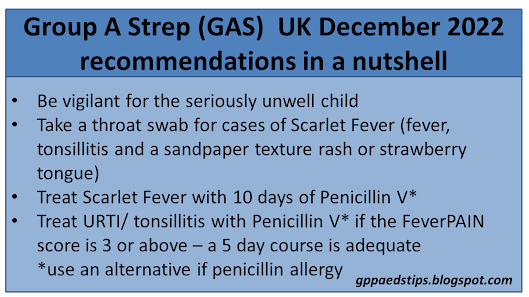

At the time of publication, the UK is experienced the effects of an increase in cases of group A streptococcal (GAS) infections in children. Scarlet Fever cases are more prevalent and there are more cases of invasive infection than in an average year. Most importantly the number of deaths in children related to GAS infection is high and the associated news coverage has been significant.

When our clinical landscape changes, the question should always be: What has changed and what should I be doing differently? Let's look at each element of practice around GAS infections and see what has or should have changed.

Recognising the seriously unwell child

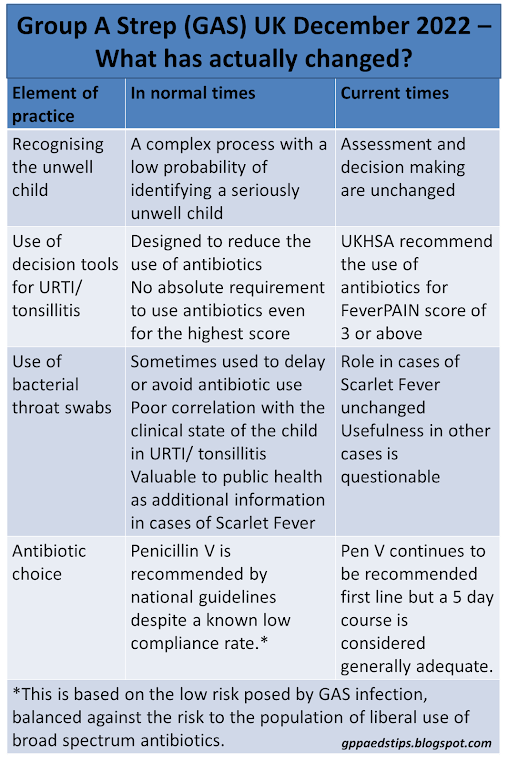

The clinical task of recognising the unwell child is actually business as usual. It remains the case that the vast majority of children who are unwell have uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infections with very low likelihood of developing complications or invasive infection.

The UKHSA has stated that the GAS infections are of normal pathogenicity which in the UK means very low risk of complications or invasive infection. The number of viral infections circulating has also risen substantially which means that the probability of any one febrile child having GAS is likely to be similar to normal times.

In any case our task of recognising the seriously unwell child remains the same as at any other time. It is and always has been a complex business which cannot be reduced to a formula. It is also the case that any febrile child, no matter how well, can go on to develop a serious illness such as sepsis or meningitis. That has always been true and all the information we are getting suggests that the risk of that happening to a child without signs of invasive infection at the time of assessment remains very small.

Diagnosing Uncomplicated Group A Streptococcal Infection

This remains as problematic as ever. GAS infection has always been a reasonably common cause of URTI including tonsillitis. Scarlet fever aside, there is no one clinicial feature with a high predictive value for GAS infection. Decision tools such as FeverPAIN are misleadingly named because they only moderately separate children into groups with different risks of having GAS. As the score goes up the likelihood of GAS also goes up but a significant number of children will have GAS infection with a low score.

Tools such as CENTOR and FeverPAIN were never introduced to help clinicians to treat GAS more often. Quite the opposite - these tools were developed to reduce antibiotic prescribing in a culture of default antibiotic use for all sore throats.

Throat swabs are often used as a means of identifying who definitely has GAS. There are two big problems with bacterial throat swabbing though. The first is that GAS is a normal commensal in throats and can be found even in asymptomatic cases. The second is that the result takes time. Due to pressures on microbiology services that time is likely to be longer at the moment. The usefulness of a swab result two to three days into an illness is therefore questionable.

The current recommendation from the UKHSA is to prescribe antibiotics to children with a FeverPAIN score of 3 or more. Throat swabs are only recommended for cases of invasive infection, scarlet fever or diagnostic uncertainty. I have assumed that diagnostic uncertainty cannot refer to being unsure as to whether an URTI/ tonsillitis is viral or bacterial as we can never be certain in any case, regardless of FeverPAIN score.

Antibiotic Choice

This has been very interesting. The UKHSA continues to recommend Penicillin V as the first choice antibiotic both for uncomplicated URTI/ tonsillitis and for scarlet fever despite the known very low compliance rate. Pen V tastes very unpleasant and as a result less than half of children will complete a course. This recommendation to use Pen V has always been based on the low risk posed by GAS infection, balanced against the risk to the population of liberal use of broad spectrum antibiotics. The continued recommendation to use Pen V as first line implies a continuation of where we were before. The effect of antibiotics is too small to change to antibiotics with better compliance rates as the harm from using broad spectrum antibiotics is believed to be greater than the benefits.

The element that has changed the most is probably the numbers seeking a medical assessment of their child, anxieties about the dangers of GAS and an increased expectation of antibiotics. If you're already good at managing all of those things then you are equipped for this moment in time. If you're still learning how to manage anxieties then this situation will be a great learning opportunity!