This week an article was published in the BJGP, talking about the overdiagnosis of asthma.

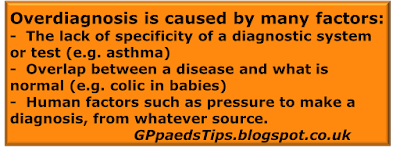

Overdiagnosis is an issue close to my heart because it causes morbidity through tests, treatments and time spent being medicalised, none of which are necessary because the patient does not have the disease. In paediatrics there is a particular tendency to overdiagnosis due to the lack of precise information (what does the abdominal pain feel like to a 2 year old? It would really help to know!) and the desire to make the child better. Being cute will have that effect.

Of course overdiagnosis is also at risk of distracting from the real diagnosis, thus robbing the patient of treatment that would be beneficial.

The above mentioned article contains some results that will make most of us sit up and take notice. Set in the four Dutch primary care centres, they found that in "more one-half (53.5%, n = 349) of the children the signs and symptoms made asthma unlikely and thus they were most likely overdiagnosed."

Very well, so essentially this shows that when you apply a new diagnostic pathway (retrospective analysis of signs and symptoms plus a generous use of tests including spirometry), it disagrees with the old diagnostic pathway, which was presumably based mainly on history and examination. That doesn't feel very applicable to the 'real world' of diagnosing childhood asthma in a front line clinical setting. Well get ready, because your 'real world' may be about to be rocked.

Earlier this year, NICE published a draft guideline for the diagnosis of asthma, including children. This contains one particular proposed recommendation that surprised me: "Do not use symptoms alone without objective tests to diagnose asthma. (in children from the age of 5)" Boom.

So, a six year old comes in with an acute wheezy episode. This was not triggered by a cold. It started when they visited an animal shelter. The child has eczema and the parents are both atopic. When you see them, the child responds to the salbutamol that you give. In further history the parents had noticed that the child coughs at night quite a lot. Time to do some tests?

I await the final version of the NICE guideline with interest. Meanwhile I am a big fan of the British Thoracic Society guidelines which stratify into three groups - low, intermediate and high probability of asthma. These guidelines list the features that make asthma more likely:

- More than one of the following symptoms - wheeze, cough, difficulty breathing, chest tightness

- Personal history of atopic disorder

- Family history of atopic disorder and/or asthma

- Widespread wheeze heard on auscultation

- History of improvement in symptoms or lung function in response to adequate therapy.

- Isolated cough in the absence of wheeze or difficulty breathing

- History of moist cough

- Prominent dizziness, light-headedness, peripheral tingling

- Repeatedly normal physical examination of chest when symptomatic

- Normal peak expiratory flow (PEF) or spirometry when symptomatic

- No response to a trial of asthma therapy

- Clinical features pointing to alternative diagnosis

Does this approach lead to overdiagnosis? I am sure that it does, for the reason that that children with intermediate probability of asthma still might not have asthma. While tests can add to the available information, the diagnosis of asthma remains clinical.

So how bad is overdiagnosis? If I could avoid overdiagnosis then I would, but in medicine that is just not possible unless there is a perfect test available. In most cases we have to set ourselves the challenge of being rigorous with our diagnoses without being overcautious. Cautiousnesses leads to underdiagnosis which is also problematic, depending on the burden of the disease. I am happy to overdiagnose sepsis in babies for example. I know that the alternative is disastrous. I am equally happy to underdiagnose colic. Colic is not harmful and there is no effective treatment.

When it comes to asthma, there is a huge morbidity and mortality associated with this disease. So while I agree with the study authors about the burden of unnecessary treatment when a child does not have asthma, I believe that the effect of moving our diagnostic goalposts needs to be considered carefully. Will there be more underdiagnosis as the pendulum swings away from making the diagnosis of asthma on clinical grounds? That is a real possibility and as far as I can tell no-one has looked at the burden of that change.

The bottom line is that asthma is a diagnosis that can be overdiagnosed and yet underdiagnosis is equally detrimental. However, without turning to complicated investigations, overdiagnosis and underdiagnosis can both be avoided by considering all the factors that make a diagnosis more or less likely as per the BTS guidelines.

Edward Snelson

Over and under most days

This post has been all about diagnosing asthma in the 5-15 year old age group. If you would like to find out more about the under five year olds you might like to read:

- How is your wheezer wired? Asthma vs Viral wheeze in the under 5 year old.

- High Voltage - What the diagnosis plus severity means for management of viral wheeze

- Looijmans-van den Akker et Al, Overdiagnosis of asthma in children in primary care: a retrospective analysis, BJGP, 1 March 2016

- Draft NICE Guideline for Consultation: Asthma: diagnosis and monitoring of asthma in adults, children and young people

- British Thoracic Society /Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network - British guideline on the management of asthma (Quick Reference Guide)