Vomiting and diarrhoea in children is usually caused by viral gastroenteritis. There are lots of myths surrounding gastroenteritis and how best to manage it. I find myself repeating things that I was once told years ago and have to check from time to time whether the 'fact' is in fact based in any reality. When I find out that it was all a myth, it makes me feel so much better when I later hear other people who hold those same myths to be true. Hopefully, between us we can dispel a few of them. Here are a few non-truths that I regularly come across:

1. It's just a virus. I know that I said it is usually a viral infection in children and that is true. However that should not fool people into thinking that it is a benign illness. Even in well nourished children, dehydration is a real risk and every year previously healthy children with gastroenteritis suffer renal failure and other consequences of severe dehydration. Avoiding dehydration makes for most of the dos and don'ts of gastroenteritis.

2. Paracetamol should be avoided because it makes the child vomit. Not so. What is more nauseating: 5 mls of liquid vitamin P or fever and abdominal pain? Giving paracetamol is likely to help resolve the vomiting and make the child feel more like they could cope with drinking a few sips of water. Certainly, children often do vomit shortly after being give paracetamol but when it works, it is well worth it.

3. You shouldn't give milk to children who are vomiting. The best fluid depends on two factors. One factor is the level of hydration. If a child is at risk of or is becoming dehydrated then oral rehydration fluid (ORF) is recommended. The second factor is the question of what the child will take. Oral rehydration is really important, so better a bottle of milk that is drunk than a bottle of ORF that is continually refused. The important thing to avoid is the list of drinks that will make matters worse. Milk is not on that list. Just because milky vomit is nasty compared to when the child is drinking clear fluids doesn't mean you should avoid milk if that is what they will take. Milk contains carbs and electrolytes and for babies it is the fluid of choice.

4. Flat cola is great for rehydration. What makes a poor rehyration fluid? Acidity to worsen gastritis as well as hyperosmolality and added chemicals that will drive diarrhoea. Flat cola ticks all of these boxes which is why it gets a special mention in the 'don't do it' bit of the NICE guidelines for gastroenteritis in the under five year olds. (1)

5. You can't give antiemetics to children. Now we are getting into more controversial territory. Antiemetics such as prochorperazine and metoclopramide (where would I have been as a house officer without these two drugs?) are traditionally avoided in ill children due to the risk of dystonic reactions. It has threfore been the case that gastroenteritis has always been in that category of illnesses that just has to get better on its own. That may be why the world of paediatrics has failed to reconsider this view despite the appearance of newer and safer antiemetics. There is good evidence for example that ondansetron reduces vomiting and may aid rehydration (2). So why don't we use that when a child is failing to rehydrate orally? NICE considered this when writing its guideline and noted that ondansetron is also associated with increased diarrhoea. The answer was therefore that it could not yet be recommended, but possibly with more research, ondansetron will be recommended in specific circumstances.

6. You can't give antidiarrhoeals to children. Again, NICE considered the pros and cons of this option. There are various types of antidiarrhoeal medicines, each of which was decided against in turn, mostly on the basis that there was no evidence for benefit. In the case of loperamide, there is reasonable evidence that it does help (3). So what's the problem? Loperamide is not licensed for use in children in the UK (and I think the same is true in the USA and Australia but I'm not sure about elsewhere). However, the BNFc does list doses and acknowledges the license issue. I don't intend to medicalise self limiting gastroenteritis, but if I thought it would help, it is good to know that it is therapeutic option.

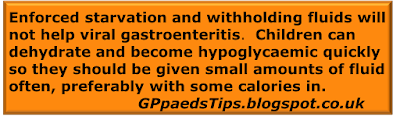

7. A period of starvation can resolve vomiting or diarrhoea. The only clinical value to an enforced period of starvation for a child is that it is a great way to diagnose MCADD. Witholding food or drink will not change the course of viral gastroenteritis. However, some children do have underlying, yet hidden metabolic disorders of energy production. These children have often had no manifestaion of their disorder because they have never run out of immediately available energy. When they are unwell and rely on ketones, everything goes wrong and hypogylcaemia can come on profoundly and unexpectedly early into a period of fasting. Any ill child who is not getting calories and who becomes subdued or agitated should have a blood glucose checked.

8. It's a 24 hr bug. In fact who knows how long it will last. I don't believe that you can make something go wrong just by saying a thing. For example, I am very happy to walk around at work commenting on how lovely and quite it is and enjoy seeing the superstitious flinch at this. However predicting the length of a gastroenteritis is a recipe for perplexed parents. Vomiting usually settles by day 3 and diarrhoea should be at least much improved by day 7. Should be...

If diarrhoea is not resolving at day 7 then consider doing a stool sample.

9. It's probably food poisoning. Thankfully not. The vast majority of vomiting and diarrhoea in children is viral gastroenteritis. Bacterial infections are more likely if the child has been to an area with endemic infection. A history of consuming foods that are likely to have been contaminated is also important. A sudden onset of vomiting does not imply food poisoning though. Norovirus for example typically causes sudden and severe symptoms.

10. Dehydration requires intravenous fluids. Rehydration is best provided through the gut, not a vein. Although guidelines are changing in order to avoid dangerously hypotonic fluids, intravenous rehydration will always be risky. Every effort should be made to achieve oral hydration. If this fails then nasogastric rehydration has a good evidence base.

Of course these are only the myths that I used to believe before my faith was destroyed by reasoning and evidence. Do you have any of your own? If you know of a wrong but popularly held belief to do with gastroenteritis then please post it in the comments below. Cheers!

Edward Snelson

Grade 'O' in Care of Magical Creatures at O.W.L.

Disclaimer: It feels a bit strange to be in agreement with so much of a NICE guideline. I may be coming down with something.

References

- Diarrhoea and vomiting caused by gastroenteritis in under 5s: diagnosis and management NICE guidelines [CG84]

- Szajewska H et al., Meta-analysis: ondansetron for vomiting in acute gastroenteritis in children, Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007 Feb 15;25(4):393-400.

- ST Li et al., Loperamide therapy for acute diarrhea in children: systematic review and meta-analysis, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE)