Another week, another crisis - This time, in the UK we have a major shortage of blood bottles.

Primary care have been advised to suspend non-urgent blood tests for the next few weeks during a major shortage in sample bottles. Personally, I blame the 5G mast they put up near the hospital.

When we are faced with limited resources, we have to get even better than ususal at decision making. We have an opportunity to look with fresh eyes and recognise those areas of practice which may have become facile and revisit how we use available resources. In this post, I'll be looking at the use of blood counts in children. When are these tests likely to be genuinely helpful and when are they unlikely to be the best next step?

First of all some general principles:

The last one in that list is particularly relevant to the question of when to do a blood count.A blood count gives a wealth of information about various haematological parameters. Because there are so many being reported, it is reasonably likely that any report will include one parameter that is outside of the statistical norm. One of the reasons for this is that children have very active and responsive bone marrow and immune systems. Peaks and troughs in white cells are more common and extreme in children even if well. As a result, blood counts can be historical by the time they are reported.

It is very common to find an abnormal parameter (e.g. lymphopaenia) for which the recommendation is simply “repeat”. By the time the result is known by the requesting clinician, it may well be the case that the child has made plenty more of the lymphocytes in response to the dip reported by the test.

Of course, chronic and persistent abnormalities do exist. The next question is, are these usually a surprise finding on a blood test?

The simple answer is no.

- Congenital immunodeficiency is extremely rare in children and does not usually present as a chance finding on a blood test done to investigate low-level concerns. It usually presents with severe and atypical infections and does so early in life.

- Acquired haematological problems (HIV/AIDS aside) will usually present with significant systemic signs and symptoms – chronic fatigue, pallor, weight loss or pyrexia of unknown origin.

It is notable that it is exceedingly rare for children with cancer to present via the two week wait referral pathway(1) that exists in the UK. Instead, the vast majority present via the ED or as an acute referral from a clinician in Primary Care. The likely reason for this is that there are red flags apparent to the parent or the primary care clinician. The two week wait pathway tends to be used in cases where the child has a worrying feature without serious red flags. (e.g. a solitary palpable lymph node which is not growing and in the context of a well child) In other words, when a child is pale and lethargic and looks unwell, someone makes sure they are seen immediately. Serious illness usually presents with atypical signs or symptoms.

This brings us onto another rule of thumb:

The decision to perform blood tests is sometimes a sign of uncertainty. The clinician feels unable to be completely reassured yet is not able to reach a definitive diagnosis.

To illustrate this, let me give you a clear haematological example of a blood test being done to answer a specific question:

A child presents one week after a viral illness. They are well and afebrile but now have a diffuse petechial rash. There is no lymphadenopathy, pallor or hepatosplenomegaly. The clinician considers the possibility that the child has immune thrombocypaenia purpura and does a blood count to check platelets. The blood test confirms the diagnosis.

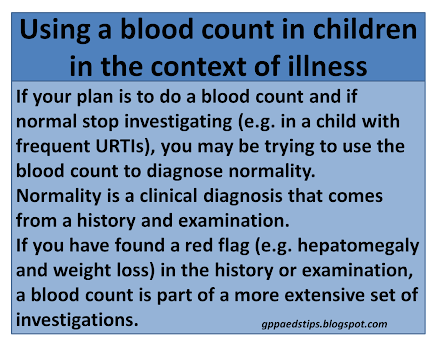

If a blood test is done without a specific question, or because the clinician hopes that the blood test with add weight to a diagnosis of normality, this is problematic. Due to the above mentioned fluctuations, there is a high probability that the result will not be completely normal. If the aim is to gain time, watchful waiting without a blood test is often the more valid approach.

The current crisis may be the perfect opportunity to ask questions about the role and importance of blood tests in children. When it comes to blood counts in children, these rarely give useful information in the absence of a pre-test clinical sign or symptom which already gives a very high probability of a haematological or immunological problem. Using a blood count to check something specific such as haemoglobin is a far more precise science. Ask a question, get an answer. Boom.

Edward Snelson

@sailordoctor

Disclaimer - Human factors may influence the decision to do a blood count. I have not included this in my analysis. Draw your own conclusions as to why this may be, human.

References

- Roskin J, Diviney J, Nanduri VPresentation of childhood cancers to a paediatric shared care unitArchives of Disease in Childhood 2015;100:1131-1135.